Key Ricardian Facts

Q. What circumstances make King Richard III such a

controversial monarch?

Richard is controversial because of the two widely differing views of him. He is known as a soldier, a statesman and a lawmaker. Even his enemies never doubted his courage in battle. He dispensed the same justice to the rich and poor alike (unheard of at the time). He took the coronation oath in English and laws were written in English for people to understand. He introduced the system of bail and tried to cut out some of the corruption in the law courts. Set against that is the Tudor version of history, which helped to prop up their shaky claim to the throne. Shakespeare's play is where most people get their 'knowledge' of Richard. In the play, Richard is portrayed as an evil monster who is prepared to use murder as a means to win the throne and then keep it. There are also many questions regarding Richard which are still not possible to answer - for instance, The Princes in the Tower. No-one knows for certain what happened to them. There is no contemporary evidence that Richard had anything to do with the deaths of Henry VI, Edward of Lancaster or his own brother George, yet Shakespeare blames him for murdering all three. Richard is also accused of murdering his wife, Anne Neville, by poisoning her. However, the Croyland Chronicler says that doctors told Richard to avoid Anne's bed, which suggests she had some sort of debilitating disease, such as consumption. The Tudors also claimed that Richard was a usurper and Henry VII went so far as to order the destruction of all copies of the Act of Parliament (known as the Titulus Regius) that legally awarded the throne to Richard. Fortunately, a surviving copy was later found in the Tower of London, proving that Richard did not usurp England's throne.

© Richard III Society - Leicestershire Branch

The Princes in the Tower

Q. Why did King Richard III lose the Battle of Bosworth?

What do we know of the circumstances of his death?

A. Given that Richard's army had superior numbers (estimated at two to one), he should have prevailed. So his defeat was in all probability due to William Stanley's intervention on Henry's side, which considerably changed the relative strengths of the two sides. There are also questions about the role played by the Earl of Northumberland. He drew up his forces behind Richard as his reserve, but took no part in the battle. Was he protecting the rear of Richard's forces from Lord Thomas Stanley, or did his ongoing power struggle with Richard in the north of England play a part in his decision? During the battle, Richard wore a gold circlet, set with jewels, on his helmet which marked him out as king. He had no intention of fleeing the field, despite Shakespeare's (in)famous speech about "a horse... a horse, my kingdom for a horse!" There are no surviving eye-witness accounts of the battle and later stories differ widely, so it's difficult to draw an accurate picture of what happened. But all seem to agree that at a critical point in the battle, Richard charged towards Henry Tudor with his household knights. He nearly succeeded in reaching him, getting close enough to kill William Brandon, Tudor's own standard bearer. However, Sir William Stanley chose this moment to come to the aid of Henry Tudor, having previously refused to commit to either side. Polydore Vergil (the official Tudor historian) and Juan de Salazar both say that Richard was urged to flee the field, but refused. Vergil wrote: "King Richard alone was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies". The Croyland Chronicler says "while fighting, and not in the act of flight, the said King Richard was pierced with numerous deadly wounds, and fell in the field like a brave and most valiant prince". Although the details surrounding his death are very sketchy, the Croyland Chronicler's account was partly corrobated by the Micro-CT scanning of the skeleton. This revealed two large wounds at the base of the back of the skull, probably delivered with a halberd or sword and likely to have been fatal. The top of the skull showed a small penetrating wound made with a pointed weapon, such as a dagger, and there were five further wounds to the skull.

Battle re-enactment at Bosworth

Q. Why was it important for the victorious King Henry

VII to keep Richard's body and bring it back to Leicester?

A. Richard's body had to be displayed so that the people knew for sure that he was dead (Edward IV did the same with the bodies of Richard [The Kingmaker] Neville and John Neville after the Battle of Barnet, displaying them outside St. Paul's for two days.) Henry Tudor's claim to the throne was 'by right of conquest' as he had very little hereditary right to the throne. Tudor's mother, Margaret, was a Beaufort and the Beauforts had only been made legitimate by Richard II in 1397 (they were the offspring of John of Gaunt and his mistress, Kathryn Swinford, who later became his third duchess). However, when John of Gaunt's son by his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster, became Henry IV, his Beaufort half-brothers were a bit too close for comfort. So although Henry IV confirmed in 1407 that the Beauforts were legitimate, he added the clause "excepta dignitate regali". Thereby declaring that the Beauforts were not eligible to sit on the throne of England. Consequently, Henry VII had a shaky hold on the throne with the crowned heads of Europe questioning his right to it. The last thing Henry needed was for people to believe Richard was still alive and prepared to support rebellions on his behalf.

Henry VII

Q. Why do some people think he was thrown over Bow

Bridge and into the River Soar?

A. In John Speede's account of 1611 it is stated that following the dissolution of the monasteries (Leicester Greyfriars was dissolved in 1538) Richard's tomb was destroyed and his remains dug up and reburied at one end of Bow Bridge. Speede gives no source for this, referring to it as a tradition. This account grew and was embroidered upon until it became accepted that "Richard's remains were dug up and dragged through the streets of Leicester by a jeering mob before being thrown over Bow Bridge into the River Soar". The story became part of Leicester folklore and legend, along with the story of Richard's foot striking Bow Bridge on the way out of Leicester to Bosworth Battlefield. The old wise woman standing by the bridge then prophesied that his head would strike it on the way back.

Bow Bridge in Leicester

Q. What format did King Richard's funeral take? Where

did it take place?

A. King Richard III was buried on 25th August 1485 in the Greyfriars church in Leicester. Both Polydore Vergil and John Rous tell us that Richard had a private burial and the grave was in the choir of the Greyfriars, at the east end of the building, close to the high altar. A document in the National Archives records that Henry VII made provision for a tomb for Richard's grave in 1494-95. The document states that the tomb was erected "In the church of Friers in the town of Leycestr where the bones of King Richard iijde reste" (TNA, C1/206/69 recto, lines 4 & 5) We now know that the grave was not dug sufficiently long enough to accommodate Richard’s body so his head was propped up and the sides of the grave sloped inwards towards the bottom. There was no evidence of a shroud or a coffin. We do not know what format Richard's funeral took, but can only assume that the friars would have performed the usual offices for the dead at the time. It would have been a catholic ceremony as it took place before the Reformation.

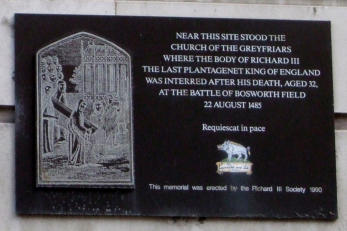

A plaque in Greyfriars Street indicates

that Richard’s body was buried nearby

Q. Why was the site of King Richard's grave lost?

A. John Speede's map of 1610 incorrectly labelled St. Martin's Church (now Leicester Cathedral) as the Greyfriars. It was actually the Black or Dominican Frairs. Greyfriars lay to the east of St. Martins, as per Thomas Roberts map of 1741. This explains why John Speede states that Richard's grave-site was "Overgrown with nettles and weedes... very obscure and not to be found". He was looking in the wrong place! Christopher Wren, later Dean of Windsor and father of architect Sir Christopher Wren, wrote that he had been shown Robert Herrick's garden in 1612: "At the dissolution [of the Greyfriars] where of the place of his [Richard III's] burial happened to fall into the grounds of a citizen's garden, which being afterwards purchased by Mr Robert Herrick (some time mayor of Leicester) was by him covered with a handsome stone pillar, thrice foot high, with this inscription - Here lies the body of Richard III, some time King of England." Over time, the site gave way to Georgian houses and roads, Victorian buildings and Alderman Newton Boys School, but as John Ashdown-Hill wrote in 2010: "The fact that Herrick's pillar stood in his garden indicates that the location of the grave continued to be in open ground well into the 17th century, while nowadays, the grave-site may well be covered in tarmac." John certainly got that right!

Richard’s re-interment in 2015 took place with all the

dignity and honour that was missing at his burial

Q. Was King Richard married and did he have any

children?

A. Richard married Anne Neville, daughter of Richard Neville (aka Warwick the Kingmaker), between 1472-73. Their only surviving child was a son called Edward, who was born between 1474-76. Young Edward died in 1484. Queen Anne died on 16th March 1485 and was buried in Westminster Abbey. Prior to his marriage, Richard had two illegitimate children: John of Gloucester and Katherine Plantagenet. John was knighted in York Minster on 8th September 1483 (when his half brother, Edward of Middleham, was invested as Prince of Wales). John was appointed Captain of Calais on 11th March 1485. Henry Tudor removed him from this position when he became king. Katherine Plantagenet became the wife of William Herbert, Earl of Huntingdon, in 1484. However, Katherine had died by 25th November 1487 when the Earl was described as a widower. Katherine was probably buried in St James Garlickhithe in London. A possible third illegitimate child was Richard of Eastwell, but that remains speculative. The mothers of John and Katherine are unknown and we are not aware of either of them having any children of their own.

Richard’s wife, Anne Neville

Q. Why did Shakespeare portray King Richard III as such

a villain?

A. Shakespeare's play, Richard III, was written in the early 1590s during the reign of Elizabeth I, Henry VII's granddaughter. Shakespeare obviously wanted to please the queen with a version of history that made her family look good and Richard III look bad. The play was the culmination of 100 years of propaganda against the last Plantagenet king and was based on the character 'created' by Sir Thomas More, who was one of the earliest exponents of the 'Tudor myth' about the life and character of Richard. In any event, Shakespeare was a playwright, not a historian. To him, the drama of the piece would have been of infinitely greater importance than a meticulous attention to historical truth. He wanted to create an out-and-out villain that audiences would be fascinated by, so he exaggerated Richard's curvature of the spine (scoliosis) to create the impression he was a hunchback and then added to the effect by falsely giving Richard a withered arm and a limp. To Elizabethan audiences, who believed that deformity was synonymous with evil, this was an obvious sign of Richard's role as the villain of the play.

Sir Thomas More, who created many of the

myths about Richard

Q. Was he a 'hunchback' with a withered arm?

A. Scans of Richard's skeleton show he only had a slight deformity that would have barely affected his appearance or prowess on the field of battle. A 3D reconstruction of the king’s spine shows 65 to 85 degrees of ‘scoliosis’, or sideways bending of his spine to the right. The condition, which would have developed in his early teens, means he was not a hunchback at all Despite having one shoulder slightly higher than the other and a short trunk in comparison with his arms and legs, there is no evidence he walked with a limp or had a withered arm. The ‘well balanced curve’ of his spine could have been concealed by a good tailor and custom-built armour. Unlike the hunchback depictions seen on stage and screen, his head and neck would have been straight, not tilted to one side. Dr Jo Appleby, from the University of Leicester’s School of Archaeology and Ancient History, who led the research, said: "Although the scoliosis looks dramatic, it probably did not cause a major physical deformity. This is because he had a well-balanced curve. The condition would have meant that his trunk was short in comparison to the length of his limbs, and his right shoulder would have been slightly higher than the left, but this could have been disguised by custom-made armour and by having a good tailor. "A curve of 65-85 degrees would not have prevented Richard from being an active individual, and there is no evidence that Richard had a limp as his curve was well balanced and his leg bones were normal and symmetric." Previous research suggests Richard III would have been about 5ft 8in tall without his deformity, about average for a medieval man. But his condition meant he would have appeared slightly shorter.

Dominic Smee has a form of scoliosis similar to

King Richard’s and for a Channel 4 documentary,

“Richard III: The New Evidence”, Dominic was

subject to various riding and training tests that

showed the condition would not have had any

negative effects on the king’s ability to fight in

battle.

Richard III Society

Q. How closely do the events of the play, Richard III,

mirror the historical facts?

A. Not closely at all. Shakespeare has many things completely out of time sequence and has Richard murder many people on his way to the throne. According to the play, Richard is responsible for his brother George's death (the order would have come from Edward); Henry VI's death (the order would have come from Edward); his wife Anne's death (she had been ill for some time, possibly with consumption); and the death of Anne's first husband, Edward of Lancaster (he died in battle). In addition, he is supposed to have murdered the Princes in the Tower - but their fate still remains an unsolved mystery. Nobody knows for certain whether they were murdered, disappeared, or even survived. Richard has been accused of ordering their deaths even though there is no direct evidence to convict him. Similarly the Duke of Buckingham, Henry VII, Margaret Beaufort and the Duke of Norfolk have also been suspected of committing the crime, but once again there is no direct evidence to convict them. Shakespeare also has a number of events happening at the same time, which in reality happened some years apart: * George, Duke of Clarence is arrested and subsequently executed (this occurred in 1478). * King Henry VI's corpse is taken to Chertsey Abbey (he died in 1471). * King Edward IV is ill (1483) * Margaret of Anjou - Henry VI's queen - is still at court arguing with Richard. Yet she returned to her native France after the Treaty of Picquigny in 1475. In the play, Richard is still at court when Edward IV dies (9th April 1483). He actually left London after the conclusion of parliament on 20th February 1483 and was back in Middleham when Edward died. According to Shakespeare, Edward IV is pre-contracted in marriage to a Lady Lucy, but in reality the pre-contract was with Lady Eleanor Butler, the daughter of Lord Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury. Richard had no intention of fleeing the field of battle at Bosworth and was determined not to go into exile again. He would live or die that day as England's king. He did not say "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!" Nor for that matter did he fight Henry Tudor in single combat, although he did get close enough to kill William Brandon, Tudor's standard bearer. No one doubted Richard's courage. Even the official Tudor historian Polydore Virgil wrote "King Richard, alone, was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies."

Q. Does Yorkshire have a better claim than Leicester to

King Richard's remains?

A. When human remains are found, it is normal archaeological practice for them to be re-interred in consecrated ground within the same parish (Leicester Cathedral, then known as St. Martin's Church, is less than 100 yards away from Richard's original burial place). The Judicial Review that took place in 2013/14 found that procedures relating to the archaeological dig and the plan to re-inter in Leicester Cathedral had been followed correctly and dismissed calls for a review of where the reburial should take place. Richard did not leave any record of where he wished to be buried. Had he done so, it is possible he might have chosen either Windsor or Westminster Abbey - the burial places of kings. Richard buried his wife, Anne, in Westminster Abbey (not York Minster) as Queen of England. He was a pious man and endowed many religious houses. He also endowed a chantry at York Minster, but that does not necessarily mean he intended to be buried there.

Shakespeare’s play was far from an accurate

portrayal of the facts

York Minster

Q. Was Richard a usurper?

A. No. When Edward IV died on 9th April 1483, his 12-year-old son, Edward, became king, with Richard assuming the role of Protector of the Realm during his minority. During that summer, Richard was informed by Bishop Stillington of Bath and Wells that Edward IV had not been legitimately married to Elizabeth Woodville. The Bishop had knowledge that Edward had made a secret marriage with another woman, Lady Eleanor Butler, the daughter of Lord Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, before marrying Elizabeth. As Edward's marriage ceremony with Elizabeth had also been a secret affair, it appeared only too likely that the allegation was true. Secret marriages were unlawful by church law, but not invalid, so the first marriage made the second one null and void. It followed that the children born of Edward and Elizabeth were illegitimate, and specifically, that their eldest son could not inherit the Crown. The matter was subsequently debated in parliament, which accepted the allegations were true and offered Richard the Crown through the Act of Titulus Regius. He was duly crowned King Richard III on 6th July 1483 in Westminster Abbey and his wife Anne was crowned Queen at his side. The coronation was attended by nearly all the nobility of England and was a magnificent occasion. After Richard was overthrown, the Act was repealed by the first parliament of the new king, Henry VII. Henry also ordered his subjects to destroy all copies of it (and all related documents) without reading them. So well were his orders carried out that only one copy of the law has ever been found. This copy was transcribed by a monastic chronicler into the Croyland Chronicle, where it was discovered by Sir George Buck more than a century later during the reign of James I.

Parliament decided that Edward IV’s marrage to Elizabeth

Woodville had been bigamous

Leicestershire Branch

Battle re-enactment at Bosworth